The Winter War began in November of 1939, when the Soviets invaded Finland, seeking to claim Finnish territory. With overwhelming numbers advantages in men and firepower, the Soviets were expecting victory in a couple of weeks. Instead, the conflict went on for three months, with the Soviet soldiers taking casualties at a rate five times that of the Finnish forces. While Finland ultimately agreed to sign 11% of its land over to the Soviets in the peace treaty that ended the war, Finland retained its sovereignty and demonstrated that it was no easy target. Nikita Khrushchev characterized the advantages the Soviets had, noting, “But on these most favorable terms, we could only win through huge difficulties and incredibly great losses. In fact, this victory was a moral defeat.”

So how did tiny Finland, dramatically outgunned and outmanned, with soldiers who looked like they’d be more at home in Santa’s workshop than on the battlefield, give the Soviets so much more of a fight than anticipated? Below are 10 ingenious ways the Finnish forces fought off the Soviets to deliver this “moral defeat.”

10. They ate well… and made sure the Soviets didn’t

The Winter War certainly proved the old saying that “An army marches on its stomach.” Finnish soldiers did pretty well in the food department. The Lotta-Svärd, an organization of Finnish women who supported the war effort, managed catering efforts for the troops. Lotta-Svärd volunteers staffed small mobile field kitchens, sometimes pulled on sleds, to provide hot meals to soldiers. Almost every unit had its own field kitchen, staffed with Lotta-Svärd personnel, who accompanied the soldiers everywhere. Caterers even carried their own firearms when their units were in combat zones. Additionally, local Lotta-Svärd chapters operated Baking Units, which produced 200,000 kilograms of bread per day for Finnish troops.

Mindful of the value of a hot meal and a full stomach, Finnish soldiers worked diligently to deny the same to their Soviet opposition. Finnish soldiers targeted the much bulkier Soviet field kitchens for attack, depriving their adversaries of the sustenance of hot food and hurting morale. Hungry Soviet soldiers were responsible for one of the war’s oddest episodes, a battle that came to be known as the “Sausage War.” The Soviets launched a surprise nighttime attack on Finnish artillery and supply columns, which were very lightly defended at the time. The initial attack was successful, but lost momentum when starving Soviet soldiers spotted bubbling pots of sausage soup the Finnish had abandoned as they fled. As the Soviets tucked into the hot stew, the Finns regrouped, halting the Red Army’s advance and killing over 100 Soviet soldiers, some of whom died with bits of sausage still in their mouths.

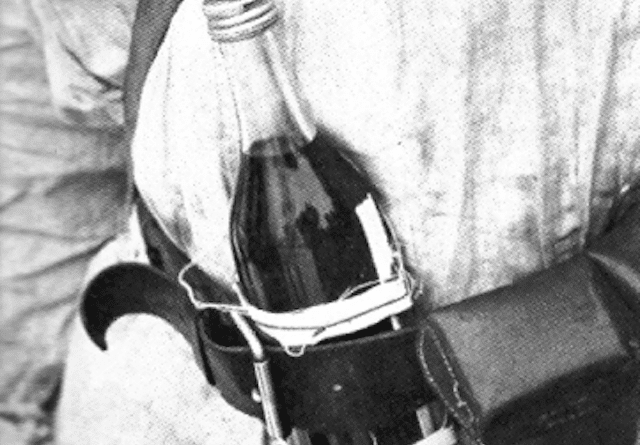

9. They used (and coined the name) Molotov cocktails to neutralize Soviet tanks

The invading Soviet army had 100 times more tanks than the Finns, who had less than 40 tanks, some of which were obsolete. The Finns also didn’t have much anti-tank artillery at their disposal. What they did have was the ingenuity to use simple materials to negate the Soviet tank advantage. They built improvised explosive devices, using a bottle with some flammable material inside and a rag fuse, which when lit and thrown, would ignite the combustible contents upon impact. The tanks of the era had ventilation hatches and when these flammable bottles were chucked into them, the fire, smoke and heat they created within the confined environment of the tank drove the soldiers outside, where the Finnish forces could face them on more even footing.

While this type of device had been used in previous conflicts, the Winter War is when it became known as the Molotov cocktail. It was named (derisively) after the Russian Commissar of Foreign Affairs, Vyacheslav Molotov, who the Finns blamed for starting the Winter War. At the outset of the war, the Soviets blanketed bombs and incendiaries on Finland’s capital city, Helsinki. When Finnish news sources reported these attacks, Molotov denied them and said the Soviets were merely delivering food aid to starving Finns. The Finns, who knew this wasn’t the case, began referring to multiple incendiary devices as “Molotov breadbaskets.” When the Finns started deploying their anti-tank bottle bombs, they dubbed them “Molotov cocktails,” saying they were serving up a “drink” to pair with the Soviet “breadbaskets.”

8. They had the “White Death”

What is “The White Death”? A better question might be, who is “The White Death”? The answer is surprising. Prior to the Winter War, if you encountered Simo Häyhä, he probably wouldn’t strike you as someone who warranted a fearsome nickname. An unassuming Finnish farmer, Häyhä stood only 5-foot-1, and was in his mid-30s when the war broke out. Nonetheless, he managed to become the most prolific military sniper in history, reportedly killing 505 Soviet soldiers during the 3-month duration of the Winter War.

Häyhä had enjoyed hunting as a hobby before the war, and his exceptional marksmanship as a sniper quickly became infamous amongst the terrified Soviet forces, who called him “The White Death,” perhaps because of the winter white coat and hood he wore to camouflage himself. Häyhä did his best to blend into the frozen landscape, preferring iron sights for his gun to avoid having the sun’s glare reveal his position and chewing snow to prevent his warm breath from being seen. While the Soviets tried numerous times to take Häyhä out, even when they finally succeeded in shooting him in the head, the Soviets could not stop “The White Death.” The day the Winter War ended, Häyhä emerged from a coma and was cheered as a national hero. Despite his exceptional performance as a sniper, Häyhä remained modest, saying, “I did what was asked as well as I could. Finland wouldn’t exist if everyone hadn’t done the same.”

7. They had saunas

Saunas? In front-line combat? The idea may seem ludicrous at first glance, but saunas are an integral part of Finnish culture. In Finland, saunas outnumber households by a ratio of more than 2 to 1 and 99% of Finns visit a sauna at least once a week. Finnish soldiers were ready to fight to the death to defend their homeland, but they certainly weren’t going to do it without saunas. Every two to three days, if combat conditions permitted, each Finnish soldier was scheduled for a turn on one of the frontline saunas.

In addition to utilizing the village saunas that are a constant across Finland, Finnish troops had mobile saunas for themselves and their equipment. In addition to providing an obvious morale boost and a reminder of the culture they were fighting for, the saunas were useful in preventing frostbite and killing bacteria, reducing the incidence of disease.

6. They divided and conquered

In the Finnish language, motti means a bundle of firewood. During the Winter War, this word took on a new meaning, as Finnish troops, greatly outnumbered by their Soviet counterparts, sought to divide Soviet units into isolated pockets called motti, which could then be surrounded and dealt with individually by Finnish soldiers. As one German military liaison to the Finns summarized it, “Finnish tactics aim to penetrate the front of the enemy, to separate the enemy’s strong points from each other, to cut off these strong points completely from all arteries of supply, and to encircle them.”

The motti strategy was abetted by the Soviets’ use of heavy equipment. Large mechanized Soviet convoys were forced to travel in large columns across Finland’s few major roadways. This left them vulnerable to ambushes from more nimble Finnish forces, who sometimes felled trees to separate Soviet convoys into more manageable motti. Once they were divided into pockets, the Finns were able to starve Soviet soldiers of supplies (including food), while launching intermittent attacks, ultimately defeating these small groups and claiming their artillery. This tactic was effectively deployed in the Battle of Suomussalmi, where Finnish troops triumphed, successfully defending the city of Oulu, though they were outnumbered more than 4 to 1 by Soviet soldiers.

5. They used psychological warfare

Because they could never overcome the Soviet advantage in sheer volume of manpower, Finnish troops knew that they needed to demoralize the opposition. Finnish tactics focused on keeping the Soviet troops off balance, depriving them of any relief from the misery of war, and ensuring a constant state of fear amongst Soviet troops. In addition to the use of improvised explosives, snipers scattered throughout the wilderness, and the motti strategy, the Finnish employed other tactics to strike terror in the heart of their enemies. Much of the territory abandoned by Finnish troops was booby-trapped with bombs and mines, meaning a constant state of anxiety and a slow pace were features of any Soviet advance. Additionally, the retreating Finns destroyed civilian shelters as they left, denying the Soviet soldiers a place to rest.

During the war, Soviet casualties were heavy and, on occasion, Finnish forces propped up the frozen dead bodies of Soviet troops as a warning to their comrades. If the sight of the bodies of their fellow soldiers wasn’t enough to keep Soviet soldiers awake at night, the ambush night attacks launched by the Finns ensured that sleeplessness was a constant for the Soviet forces, leading to diminished morale, lowered immunity to disease and frostbite, and duller reflexes. The presence of Finnish snipers meant that bonfires were also a very risky proposition, so most Soviet forces endured the long, cold winter nights with little relief from the frigid air. The Finnish dropped leaflets from the air over the Soviet forces, offering cash payments for weapons and surrender and depicting Soviet soldiers enjoying their lives post-surrender. Others mocked Soviet leadership and highlighted the gruesome losses the Soviets had suffered during their war with Finland.

4. They used reindeer and sleds

While the Soviets relied on tanks to cover ground, Finnish defense forces used reindeer, pack horses, and sleds for transport. While this was largely a matter of necessity (the Finns did not have access to many tanks), it was also a much better method of traversing Finland’s harsh winter terrain. Special deep-snow horse-drawn sleighs called ahkios were used, demonstrating usefulness well beyond getting to grandmother’s house. Ahkios were used to transport the wounded, haul munitions, and even as firing platforms for machine gunners. The sleighs were pulled by pack horses, and particularly in Finland’s frigid Lapland region, by reindeer.

Most of these animals had been repurposed from logging and farming operations and were used to pulling heavy loads in sub-zero temperatures. Using multiple reindeer, a sleigh could haul 650 pounds of gear, and the reindeer had the stamina to pull this weight for up to 8 hours at a time. In addition to being able to navigate well off-road, the sleighs offered another major advantage over tanks: stealth. By not employing motorized convoys, Finnish soldiers were able to stay quiet, retaining the element of surprise when challenging their Soviet counterparts. During WWII, the Soviets, having learned from the Winter War, would develop their own reindeer units as part of their military strategy.

3. Finnish soldiers knew the terrain, and how to navigate it

While they were outmanned and outgunned, the Finnish troops did have the home-field advantage, which they maximized. The Finns viewed the winter not as an impediment, but as an ally in defending their country. While almost all Finnish soldiers were experienced skiers, the Soviet soldiers lacked both decent skis (when Finnish soldiers captured Soviet skis, they employed them as firewood because of their inferior construction) and, for the most part, skiing ability.

As winter intensified, Finnish soldiers were able to maintain excellent mobility through skiing, including over frozen lakes and rivers, able to launch ambush attacks on Soviet forces before gliding off into the woods. Because of their familiarity with the terrain, Finnish soldiers were also able to effectively launch nighttime raids on Soviet units. In addition to further depressing Soviet morale through these raids, the ability to navigate was a significant advantage because of the lack of daylight during most of the day during winter in Finland.

2. They dressed for success

The winter of 1939 was a very cold one in Finland, with temperatures hitting -30 degrees F on multiple occasions. While both sides anticipated the frigid conditions, the Finnish soldiers were aided by their clothing, while the Soviets were hampered by their uniforms.

Finnish troops dressed in layers, generally wearing their own warm long underwear and sweaters under their uniforms, removing layers as needed to avoid excessive sweating while cross-country skiing. They also wore lightweight white snow capes over their uniforms, helping them blend into the snow. In contrast, the Soviets wore khaki uniforms and utilized army green tanks, making them stand out even more prominently against the snow, providing unintentional assistance to Finnish snipers.

1. They had sisu

Sisu is a Finnish word that lacks a precise English equivalent, but it means a certain kind of resilience, grit, and strength of purpose, particularly when confronted with adversity. This characteristic predates the Winter War by hundreds of years, long having been a central tenet of Finnish culture—the ability to persevere where others might give up.

Sisu influenced all of the other aspects of Finland’s ability to force a stalemate during the Winter War: their soldiers weren’t cowed by the Soviets’ advantages in numbers and firepower, they maximized their few advantages, they developed novel tactics to dull the impact of the Soviets’ strengths, and an understated, small-statured farmer became one of the most lethal military snipers in history. While the Soviets had significant military advantages at the conflict’s outset, by the end, they undoubtedly understood that they had failed to account for the Finns’ sisu when they had planned for a quick and easy conquest.

3 Comments

My compliments to the author. This is a fabulous list!

What incredible stories and facts! And I can’t believe how many saunas they have! Crazy

I wonder if they really did treat surrendering enemies with mercy and generosity. It wouldn’t surprise me, because that’s proven to be a VERY effective tactic when trying to gather intel from captured enemies. Start pulling out fingernails and screaming threats of worse to come and you validate every rotten thing their leaders have said about you. Treat them with dignity and empathy, and they start to wonder who “the bad guy” is in this whole operation.

So why don’t more people use this technique when it works so well? Unfortunately, too many people (especially those in charge of things like “POW interrogation) are sadistic brutes who are less concerned about “getting results” than they are about scratching that primitive itch for vengeance.