For nearly one thousand years, the world quaked at their footsteps, and the very sound of their name: The Legions. The elite troops of Rome’s formidable army, which would carve up an empire that stretched from the Highlands of Scotland to the scorching deserts of the Arabian Peninsula. They would kill and enslave millions, pillage and raze cities to the ground, and transform the mighty Mediterranean Sea into the Empire’s own private lake. The only time in human history when the whole of the Mediterranean would be under one single government was under Roman rule. The Roman Legions were such a mighty force in the world, even their own Emperors were afraid of them.

10. Their Military Training

The Roman Legions had come a long way since around 700 BC, when Rome itself was nothing more than a small gathering of hovels atop the Palatine Hill, to 117 AD when it became the largest Empire of the ancient world, making up 20% of the world’s population. Back to around Rome’s beginnings, its army was only comprised of local farmers, who would be hurriedly called into action, fighting skirmishes with neighboring settlements. And only the men who owned property were called into battle, as they were the only ones trusted to defend Rome, or fight on its behalf.

All of this would change in 390 BC however, when an army of Gauls utterly defeated the Romans, and then descended upon the city itself. They continued sacking and pillaging Rome for the next 6 months until finally they were paid off to leave. The Romans got a wake-up call which would change their destiny forever. They then spent the following centuries perfecting their Legions by systematically training and organizing a professional military machine like nobody had ever seen before.

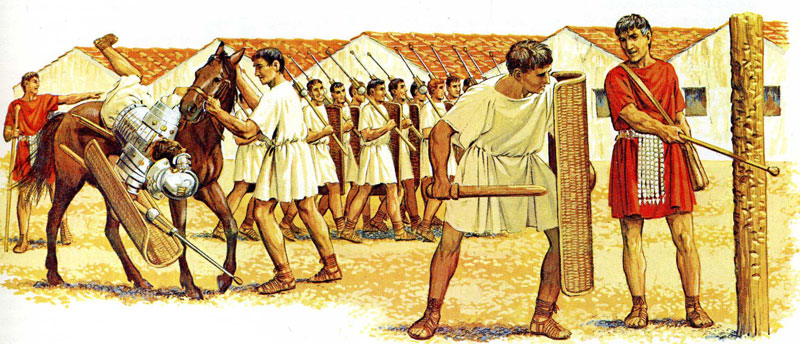

There were endless drills, and marches to the point of exhaustion. Roman soldiers were attending weapons training every morning and practiced melee combat with wooden swords, spears and shields, twice as heavy as their real counterparts, to build up strength. Part of their daily training also involved a 19 mile-long march to be completed in five hours, while carrying a full pack of weapons, shield, food rations, cooking supplies, and a short spade, along with their own personal kit. Besides these extraneous exercises, soldiers would also familiarize themselves with the highly organized battle tactics and formations, which in the early days of the Republic, at least, were based on those of the Greeks. No other army in the world at the time would receive such a rigorous training, which gave the Roman Legions a tremendous advantage in waging war.

9. Discipline Through Fear

Following orders to the letter and not questioning one’s superiors is something which most don’t naturally have built into their consciousness. So, another integral part of their training was the sense of discipline and obedience, instilled through fear. Severe punishments for even the slightest of offenses was something common within any Roman Legion. Soldiers would often times be stoned to death by their comrades for cowardice in battle or even for falling asleep at their posts while on sentry duty.

Minor offenses were handled by the Centurions (military officers), who always carried vine branches in order to strike at their Legionnaires. And since these officers were held directly responsible for the behavior of the men serving under them, whippings were commonplace in a Roman military camp. In The Annals, Tacitus talks about one such Centurion, Lucilius, who acquired the name “Cedo Alteram,” which loosely translates to “bring me another.” Lucilius was notorious for the frequent and violent beatings he inflicted on his men, breaking one vine on their backs after another, and then calling out for more. Tacitus also mentions that this particular Centurion was killed during a mutiny.

In any case, this ruthless treatment nevertheless proved useful time and time again, as the men became more reliant and trusting of each other for their very survival in the extremely harsh conditions they endured at the fringes of the empire. In short, this discipline instilled through fear gave Roman soldiers a far better chance at survival if they blindly obeyed their superiors, than if they did not.

8. The Decimation

One particularly brutal punishment for any Legion was the Decimation, which was as bad as it actually sounds. The word itself comes from this Roman military disciplinary measure, used on large groups of soldiers guilty of capital offenses like mutiny, treason, or desertion. Decimation is derived from Latin meaning “removal of a tenth.”

The way they went about it was to have the guilty men divided into groups of ten, and to have them draw straws. The soldier who drew the short straw was to be killed by the other nine, by clubbing him to death. That’s some messed up psychological conditioning right there. And since the decision of who will die was left to chance, all soldiers were liable for execution, regardless of their level of involvement, rank, or distinction. But because killing off ten percent of the army is almost never a good idea, the Decimation never became common practice.

Dionysius of Halicarnassus called it “an ancestral punishment,” and it was most prevalent during the 5th century BC, but even then there are only a few known cases. The Roman commander and future triumvir, Crassus, is said to have revived it when fighting Spartacus in 71 BC. The last recorded case of Decimation was during the reign of Emperor Diocletian (284–305 AD), but with the emergence of Christianity, this punishment disappeared completely under its influence.

7. Weapons and Armor

In the beginnings of the Roman army, only the wealthy could afford to own a sword, a shield, and probably a helmet. They became the officers of the early Legion, while the commoners, who could only afford slings and stones, became the foot soldiers. But as Rome expanded its borders, so did the army become more standardized, with the equipment being provided by the state. Their first line of defense was the chainmail shirt. The Romans may have borrowed this technology from the Gauls during the 3rd century BC. The main advantages of the chainmail (Lorica hamata in Latin) were its light weight, and that it offered good protection against slashing swords. During the 1st century AD however, the chainmail was partially replaced by segmented plate armor, Lorica segmentata. Though heavier and with a higher maintenance, plate armor offered a great deal more protection against piercing attacks.

The Roman helmet was redesigned and improved over the centuries, having Etruscan, Greek and predominantly Gallic influences. It was fashioned in such a way as to offer maximum protection, but without blocking the senses. It had large cheek pieces as to protect the side of the face, but not to cover the ears, so the soldiers could hear the commands given by the Centurions. The crests, often times made out of horsehair or sometimes feathers, had the purpose of making the wearer appear larger and fiercer, as well as to distinguish between the ranks. Centurions wore the crest across the helmet, so as to be easily distinguished in the heat of battle.

Further protection came from the Roman shield. Smaller and rounder in earlier times, the Scutum developed later into a rectangular one. It was made of layers of wood glued together and covered with leather and metal. The shield was also curved, thus offering more protection to the sides. Due to its size, the shield was also used as an offensive weapon, and worked perfectly in combination with the Gladius; the Roman short sword. While in close combat, a broadsword would become more of a hindrance since there wasn’t enough room to move it around. And when the barbarians were waving them over their heads in a sign of defiance, a Roman soldier would just stab him in the gut with his short Gladius.

6. Battle Tactics and Formations

What truly made the Roman Legions the best fighting force throughout the ancient world, were the structured nature of the army, and the formations they used in battle. A Legion was comprised of 4,800 men, divided into 10 Cohorts of 480, which in turn contained 6 Centuries of 80 soldiers, each commanded by a Centurion. This highly structured form offered the army both unity among the ranks, as well as a great deal of coordination on the battlefield. Most of the barbarians the Romans were in conflict with fought in loose arrangements and each warrior sought individual glory. But every one of the 4,800 soldiers in a Roman Legion had a precise role to play in a master strategy.

A typical assault would begin at long range, using catapults to shower the enemies with boulders and iron bolts. Next the Legionnaires would launch their javelins. Made of a wooden handle and a long iron head, the Pilum, as it was called by the Romans, would bend on impact, preventing the enemy from throwing it back. Then the soldiers would stand shoulder to shoulder, swords out, and begin their advance as a moving wall of death and destruction. With the shield extending from their chins almost down to their ankles, there wasn’t much a group of disorganized tribesmen could do.

In case of volley fire, or when advancing towards an enemy fortress, the Romans would quickly deploy their famous Tortoise (Testudo) formation. The soldiers in front and on the sides would interlock their shields, while those in the center raised them over their heads. This way they would minimize the damage done by any projectile weapon thrown against them. Another good offensive tactic was the Wedge. Here the Legionnaires formed up a triangle, and with their swords out, they would charge at the enemy, in an effort to break up their lines and divide them up. Even if the Gauls, the many Germanic tribes, or the Dacians were able warriors in their own right, none of these peoples were prepared to face such a well-coordinated, highly militarized and devastating force bent solely on domination.

5. Sea Battles Fought on “Land”

The Roman Legions themselves were predominantly infantry-based and fought mostly with sword and shield in hand. Archers and cavalry were employed into the ranks as auxiliaries from non-Roman tribes. Archers mostly came from Syria, Scythia (the Black Sea) and Crete, while mounted infantrymen came from tribes that had a good tradition of horsemanship. After a period of 25 years serving in the army, these men would finally be granted Roman citizenship. A similar shortage of skilled soldiers came in the form of sea warfare. As Rome took control of most of the Italian Peninsula, they turned their attention out to sea. Here they met the Carthaginians and in 264 BC the First Punic War had begun. This 23-year-long conflict between the two Mediterranean super powers was fought over control of the strategically-important islands of Sicily and Corsica.

While Carthage boasted a sizable military fleet, Rome did not. Nevertheless, the Romans quickly countered that disadvantage by building their own navy following a design stolen from the Carthaginians themselves. Still lacking any real seafaring experience, and while waiting for the ships to be built, the Legionnaires began practicing rowing in unison while still on dry land. After a few practice runs up and down the Italian coast, they went on the offensive. But unbeknownst to the Carthaginians, they still had an ace up their sleeve.

Since they were expert melee fighters, they came up with an ingenious invention to turn sea battles into land battles. This secret weapon came in the form of the Corvus, a boarding bridge 4 feet wide and 36 feet long, which could be raised or lowered at will. It had small railings on both sides and a metal prong on its backside, which would pierce the deck of the Carthaginian ship and secure it in place. With it the Romans were able to defeat their enemy and win the war. However, the Corvus could only be used on calm waters, and even compromised the ship’s navigability. As the Romans became more experienced seafarers, they abandoned the boarding bridge.

4. Bellum Gallicum

The Gallic Wars, or Bellum Gallicum, were a series of military campaigns waged by the Roman Legions under Julius Caesar against the Gauls living in present-day France, Belgium, and parts of Switzerland. These wars lasted from 58 BC to 52 BC and culminated with a definite Roman victory and expansion of the Roman Republic over the whole of Gaul. But these wars weren’t waged for the glory of Rome, per se, but rather for the political ambitions of Caesar himself. He recruited and paid his own Legions, which made the soldiers highly devoted to him, and him alone. On one occasion, when supplies were running low, he even ordered his men to eat grass, which they did without question.

When he was made governor of southern France, northern Italy and the east coast of the Adriatic Sea, before the invasion of Gaul, Caesar was in serious financial debt. To escape his economic constraints and climb the political ladder, he was eager for new conquests and plunder. His chance soon came in the form of a Celtic tribe, the Helvetii, who wanted to migrate to Gaul proper from the Swiss plateau they were occupying. Caesar refused them and decided to attack. Out of the 368,000 Celtic men, women and children, only about 110,000 managed to survive the onslaught. With his six Legions, he then turned his attention towards Gaul and slaughtered every town and village he encountered along the way.

Even though the region was home to somewhere around 15 to 20 million people, his successes were in large part due to the fact that the Gauls was a conglomeration of loose tribal armies that lacked any real discipline and cohesion. This way Caesar had to fight each band of warriors as he encountered them, and the campaign stretched on for much longer than he initially anticipated. Vercingetorix, “Victor of a Hundred Battles,” managed to finally rally the tribes against the Roman Legions, but it was too little, too late.

At the battle of Alesia in 52 BC, Vercingetorix almost prevailed against Caesar, but ultimately lost the battle. By the time the Roman conquest of Gaul had ended, over one million Celts lay dead, and another 500,000 were sent into slavery. Together with the many riches Caesar gathered from the Gauls, he ensured the loyalty of his Legions, and marched off to Rome to start a civil war for total control of the Republic. All Roman conquests, not just the one in Gaul, were brutal to the extreme. The more culturally different the conquered were, the more savage the Roman Legions became.

3. Crucifixions

The Romans were notorious for the ways in which they treated and disposed of anyone who would stand in their way against total domination. One particular way they dealt with the people they thought threatened the Roman way of life was crucifixion. This particularly brutal form of punishment was often used as a means of torture, as well as to send a message. Those people who were crucified were often times accused of sedition, or conspiracy to rebel. Jesus Christ was crucified for the exact same reason, and not for his religious teachings. The two men beside him were also considered insurgents, not thieves.

Stephen Mansfield, a New York Times bestselling author, calls crucifixion as “an act of state terror,” in that it was used by the Roman state and carried out by the Roman Legions for political reasons. The victims were severely mistreated beforehand, and then forced to carry their own crosses in front of everyone, to the place they would be left to die. This was done to send a message to everyone else watching. Though not the inventors of this horrific practice, the Romans did excel in it. During Spartacus’ rebellion in 72 BC, 6,000 captured rebels were crucified along the Appian Way from Capua to Rome. Since Rome’s population was about 40% slaves, and Spartacus and the other rebels were slaves themselves, their crucifixion was a definite message to those still living: “Do not stir dissent or this will be your end too.”

2. The Praetorian Guard

The most powerful of all the Roman Legions was the Praetorian Guard which was stationed in Rome itself. And often times, the Praetorians had the power of life and death over the Emperors themselves. They came into being as elite soldiers protecting generals during the Roman Republic. Marc Antony, Scipio Africanus, Lucius Cornelius Sulla, and Caesar himself all had such bodyguards. But the Praetorian Guard itself didn’t officially appear until Augustus became Rome’s first emperor in 27 BC. They acted as bodyguards to the Emperor, emergency firefighters, the secret police, crowd control, and even fought in the arena to show off their prowess to the masses.

But as Rome’s power grew, so did its corruption and intrigue. And the Praetorian Guard was often times right in the middle of all of it. Even though their task was to ensure the interests of the Emperor, if those interests didn’t coincide with their own, they would just replace him. Disgruntled Praetorians famously engineered the assassination of Caligula in 41 AD. Emperors Commodus in 192 AD, Pertinax in 193 AD, Caracalla in 217 AD, Elagabalus in 222 AD, and Pupienus and Balbinus in 238 AD were all killed by the Praetorians. In 193 AD, after killing Pertinax, they even put the crown up for auction. One man, Didius Julianus won by promising them each a bribe of 5-years-pay. But when he couldn’t deliver, he too was murdered 66 days later. In 306 AD, the Praetorians tried to play the role of kingmaker one last time by supporting Maxentius as the western emperor in Rome. They were defeated by Constantine at the Battle of Milvian Bridge in 312, and he then disbanded the Guard.

1. Making and Breaking the Empire

Without a doubt, the Roman Empire in all its might was made by the many Legions who fought and killed for it. The Roman Legions were also the ones responsible for the many civic building projects and roads built all throughout the lands they conquered. But in the end, the army is what brought Rome down. As we’ve seen up until now, Rome was a highly militarized society with an army of about 130,000 soldiers. One man in eight was in the army. And while in the beginning only men with property were allowed to fight for the glory of Rome, once it expanded beyond the Italian Peninsula, the ranks were open to a great deal more people. Foreigners were employed as auxiliaries, and after 25 years of fighting, they would be granted citizenship. And while the army grew, there was a hidden anger growing with it.

Since these men were not citizens of Rome, they didn’t believe in the idea of Rome and the “civilization” it brought with it; most never even seeing the city itself. Now, many soldiers had less interest in defending it, and instead making their fortune through the spoils of war. Their loyalty was no longer to the city or the Empire, but to the generals who they were serving under (like the case with Caesar and his Legions). Army generals then realized they could become Emperor just by marching into Rome, which they often did.

The 3rd century AD, also known as Military Anarchy or the Imperial Crisis, was a period in which the Roman Empire almost collapsed, due to the many civil wars, subsequent invasions, and economic crises. In just 35 years Rome had 40 Emperors. All of these were made possible as an unstoppable chain of events in the struggle for power during this period. By 395 AD, the Empire would be divided into the east and west and by 476 only its eastern part would survive. The Eastern Roman Empire would rule from Constantinople and be a dominant force in the region for the following 1,200 years, as a continuation of Rome itself.

2 Comments

There’s no such thing as “chainmail”. It’s “mail”.

all your base are belong to us.